Blow Your Socks Off

By Gareth Branwyn

April 20th, 1961. Next to the taxiway of the Niagara Falls Airport, engineers from Bell Aerosystems have set up equipment for an altogether new kind of flight. A young engineer, Harold Graham, straps a bulky contraption called a rocket belt onto his back. As Graham engages the rocket's throttle an immense blast of steam erupts from the engine. Out on Niagara Falls Boulevard a driver does a double take and wheels into a ditch as the world's first rocketman pops out of the mysterious cloud and shoots into the sky.

Originally conceived in 1953 by a wildly inventive Bell engineer named Wendell F. Moore, the rocket belt was part of an Army contract to create a "small rocket lifting device" that could improve soldier mobility and maneuverability. While the April 20th test flight and hundreds that followed were promising -- especially as jet engines replaced rockets -- other defense and aerospace priorities of the 1960s grounded further R&D.

By Gareth Branwyn

April 20th, 1961. Next to the taxiway of the Niagara Falls Airport, engineers from Bell Aerosystems have set up equipment for an altogether new kind of flight. A young engineer, Harold Graham, straps a bulky contraption called a rocket belt onto his back. As Graham engages the rocket's throttle an immense blast of steam erupts from the engine. Out on Niagara Falls Boulevard a driver does a double take and wheels into a ditch as the world's first rocketman pops out of the mysterious cloud and shoots into the sky.

Originally conceived in 1953 by a wildly inventive Bell engineer named Wendell F. Moore, the rocket belt was part of an Army contract to create a "small rocket lifting device" that could improve soldier mobility and maneuverability. While the April 20th test flight and hundreds that followed were promising -- especially as jet engines replaced rockets -- other defense and aerospace priorities of the 1960s grounded further R&D.

Harold Graham demonstrates an

experimental rocket lift.

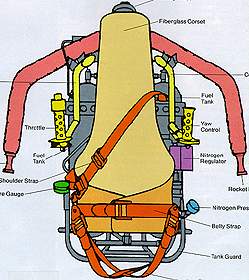

A funky thing built mainly from scrap and off-the-shelf parts, the rocket belt consisted of fuel tanks, handlebars, a control throttle and a pair of rocket nozzles. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) fuel was fed over fine silver mesh, which acted as a catalyst to produce 1,400-degree steam. The steam was then forced through nozzles to unleash 330 pounds of thrust and 135 decibels of brain-rattling sound.

experimental rocket lift.

A funky thing built mainly from scrap and off-the-shelf parts, the rocket belt consisted of fuel tanks, handlebars, a control throttle and a pair of rocket nozzles. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) fuel was fed over fine silver mesh, which acted as a catalyst to produce 1,400-degree steam. The steam was then forced through nozzles to unleash 330 pounds of thrust and 135 decibels of brain-rattling sound.

Inventor Wendell Moore observes a test run.

The belt offered a surprising degree of maneuverability -- its pilot could fly, hover, spin, negotiate tight turns and make pinpoint landings. But it was not without problems. Bill Suitor, one of the original belt pilots, recalls that during an early tether flight the control stick snapped off in his hand. He hung on for dear life as spotters yanked control ropes to keep him from crashing.

The biggest stumbling block was limited fuel capacity. The belt's recycled Air Force oxygen tanks could only hold enough H2O2 for a fleeting, 23-second flight. During one show, rocketman Suitor accelerated too quickly and discovered to his horror that he couldn't slow down. "I was at 114 feet when I looked at the fuel gauge and saw I had only a few seconds to land. I was about 3 feet off the ground when the fuel ran out."

The belt offered a surprising degree of maneuverability -- its pilot could fly, hover, spin, negotiate tight turns and make pinpoint landings. But it was not without problems. Bill Suitor, one of the original belt pilots, recalls that during an early tether flight the control stick snapped off in his hand. He hung on for dear life as spotters yanked control ropes to keep him from crashing.

The biggest stumbling block was limited fuel capacity. The belt's recycled Air Force oxygen tanks could only hold enough H2O2 for a fleeting, 23-second flight. During one show, rocketman Suitor accelerated too quickly and discovered to his horror that he couldn't slow down. "I was at 114 feet when I looked at the fuel gauge and saw I had only a few seconds to land. I was about 3 feet off the ground when the fuel ran out."

Anatomy of a hydrogen peroxide rocket belt

Despite James Bond's pronouncement in the movieThunderball that "no well-dressed man should be without one," the rocket belt never caught on. Four copies of the original Bell belt were made. Three of those are now in museums; one ended up on the scrap heap.

Nevertheless Hollywood was intrigued. A version inspired by the original Bell model and crafted in the late '60s by inventor Nelson Tyler -- who Bill Suitor says is a dead ringer for the mad scientist in Back to the Future -- saw celluloid action with Suitor, who did 007's stunt rocketeering and appeared in dozens of commercials, TV shows, movies and special events such as the 1984 Olympics. Noted Hollywood stuntman Kinney Gibson has also used the Tyler belt.

Despite James Bond's pronouncement in the movieThunderball that "no well-dressed man should be without one," the rocket belt never caught on. Four copies of the original Bell belt were made. Three of those are now in museums; one ended up on the scrap heap.

Nevertheless Hollywood was intrigued. A version inspired by the original Bell model and crafted in the late '60s by inventor Nelson Tyler -- who Bill Suitor says is a dead ringer for the mad scientist in Back to the Future -- saw celluloid action with Suitor, who did 007's stunt rocketeering and appeared in dozens of commercials, TV shows, movies and special events such as the 1984 Olympics. Noted Hollywood stuntman Kinney Gibson has also used the Tyler belt.

Despite James Bond, the rocket belt never took off.

Brad Barker of American Flying Belt recently unveiled a further modified design. He's published a technical manual and video about his RB-2000, and has offered to manufacture a rocket belt for anyone who cares to bankroll one. Though Barker's belt burns five seconds longer, Suitor and others say its advances are minor.

Still rocket belt veterans know that there's plenty of room for improvement. Rumors abound of inventors developing a new generation of jet-powered belts. "You can get up to 30-minute flights with a jet engine," says Suitor, "which could offer all sorts of uses for search-and-rescue, fire inspection, law enforcement, flying camera operators and so forth." Bell Aerospace actually licensed a jet-powered version of the belt to Williams International in 1970, but development of Bell/Williams "small lift devices" was halted after Williams' small jet engine -- the only engine of its kind -- was earmarked for exclusive use in the cruise missile.

Brad Barker of American Flying Belt recently unveiled a further modified design. He's published a technical manual and video about his RB-2000, and has offered to manufacture a rocket belt for anyone who cares to bankroll one. Though Barker's belt burns five seconds longer, Suitor and others say its advances are minor.

Still rocket belt veterans know that there's plenty of room for improvement. Rumors abound of inventors developing a new generation of jet-powered belts. "You can get up to 30-minute flights with a jet engine," says Suitor, "which could offer all sorts of uses for search-and-rescue, fire inspection, law enforcement, flying camera operators and so forth." Bell Aerospace actually licensed a jet-powered version of the belt to Williams International in 1970, but development of Bell/Williams "small lift devices" was halted after Williams' small jet engine -- the only engine of its kind -- was earmarked for exclusive use in the cruise missile.

Bill Suitor lands during the 1984 Olympics.

"It was technology 50 years ahead of its time," sighs Suitor, his voice carrying no small amount of nostalgia -- and a little bit of hope.

A L T . T E C H

Pictures: Arnold Sachs/Archive Photos | UPI/Corbis-Bettmann | Dean Conger/National Geographic Society | Courtesy of William P. Suitor | Springer/Corbis-Bettmann | Jacques Cochin/Vandystadt/Allsport |

Video: Archive Films | Courtesy of Pabst Brewing Co./Collection of William P.Suitor/Rocketman Enterprises |

Copyright © 1997 Discovery Communications, Inc.

"It was technology 50 years ahead of its time," sighs Suitor, his voice carrying no small amount of nostalgia -- and a little bit of hope.

A L T . T E C H

Pictures: Arnold Sachs/Archive Photos | UPI/Corbis-Bettmann | Dean Conger/National Geographic Society | Courtesy of William P. Suitor | Springer/Corbis-Bettmann | Jacques Cochin/Vandystadt/Allsport |

Video: Archive Films | Courtesy of Pabst Brewing Co./Collection of William P.Suitor/Rocketman Enterprises |

Copyright © 1997 Discovery Communications, Inc.